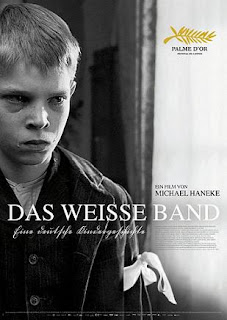

I left the auditorium of the Montgomery arthouse theater that showed Michael Haneke's Palme D'Or-winning feature, The White Ribbon, with a knot in my stomach that formed about 30 minutes into the film and only tightened for the next two hours. When I stumbled back into my car, I sat that for a moment and began to hyperventilate for a minute or so as my gut finally loosened and the flood of emotion I'd choked back for fear of having a public meltdown came pouring out in ragged breath and shaking hands. Never have I had such a reaction to a film; The White Ribbon did not so much grab me as throttle the life from my throat, and I hesitate to think what it says about me that I could go through such an ordeal and confidently say I loved it.

I left the auditorium of the Montgomery arthouse theater that showed Michael Haneke's Palme D'Or-winning feature, The White Ribbon, with a knot in my stomach that formed about 30 minutes into the film and only tightened for the next two hours. When I stumbled back into my car, I sat that for a moment and began to hyperventilate for a minute or so as my gut finally loosened and the flood of emotion I'd choked back for fear of having a public meltdown came pouring out in ragged breath and shaking hands. Never have I had such a reaction to a film; The White Ribbon did not so much grab me as throttle the life from my throat, and I hesitate to think what it says about me that I could go through such an ordeal and confidently say I loved it.The film's narration, delivered by the schoolteacher (and, in what is perhaps a self-reflexive nod, the piano teacher) of the small, fictitious German village of Eichwald, recalls that of Barry Lyndon: his address overshares detail and often beats the action to the punch, if not precluding it entirely. One may not even trust the narration; "I don't know if the story I want to tell you is entirely true," the teacher confides in us at the start. How could he? He's in a Haneke film, after all; The White Ribbon is a horror film that, with only the briefest and most somber of exceptions, never shows its horrors on-screen. However, unlike the deliberate coldness of Caché, or the condescension of Funny Games, The White Ribbon depicts violence in humanistic tones: in this film is an Austrian's attempt to figure out how the generation that preceded his could have come to accept Nazism, and as such it contains an earnestness bereft of the director's other films.

The first major action of the film -- and the only significant act that is entirely shown -- features the town doctor riding his horse into a nearly invisible wire strung across the entrance to his manor that breaks the beast's leg and severely injures the man. He spends much of the next year in a hospital 30 km away, while his children quietly persevere. The mysteriousness of this incident -- a prank? An attack of darker intentions? -- stands as the opening salvo of acts of increasing brutality and shock that mount upon the villagers. Children are kidnapped and beaten, a barn catches fire, a weakened and overworked female harvester is killed in an accident in the sawmill. Each of these instances of violence, injury and death seems self-contained, but Haneke, with his static yet probing camera, observes how those incidents not only converge but how they each alter the lives of others. No such incident, whether accidental or the result of human violence, can affect only one person.

Adding to the level of discomfort, perhaps even the violence, in the community is the town pastor (Burghart Klaußner), a hard-line Protestant who rails against the evils affecting the village and harshly abuses his children. For reasons that remain unclear, he punishes his eldest son and daughter by thrashing them with a cane, and he ties the titular ribbons on them as symbols of the innocence and purity they fail to embody. Those ribbons thus become an ironic metaphor of shackles placed upon them by their father for transgressions so ill-defined they might merely stem from the kids' existence. Later, he even shames the boy, Martin, further by intimidating the boy to stop masturbating by telling a comically ludicrous yet terrifyingly grave story of another child who withered away and died from impure touching. This pastor's behavior, his hypocritical wrath and judgment, recalls the stepfather in Fanny and Alexander, who was of course based on Bergman's own father.

The entire film is Bergmanesque, really, from Christian Berger's crisp black-and-white photography to the theatrical placement, the detailed (yet historically inaccurate) set design and emotional distance peppered with the odd, unstoppably affecting close-up. The chief connection, of course, involves religion. The pastor is one of the most ruthless people in the village, and the children he beats go on to enact violence themselves. When his mother gives birth, Martin swears and punches his slightly younger brother, as if the thought of another child being raised and tortured in this house in unbearable, or that he simply does not want more competition. As God's representative, he inflames the tempers of not only his children but the townspeople; he routinely attributes grandiose levels of evil to mendacity and other minor sins while his own use of physical and psychological torture never gives him a moment's inner conflict.

Tracing this line a bit further, one could then accept the pastor's superior, the harsh, distant baron who rules the town, as a God substitute. He does not allow his subjects, particularly the poor, migrant farmers most reliant upon him, to ever really interact with him, and he even literally works some of them to death for his own profit. When his son is taken and severely beaten, (make the connection yourself), the Baron abandons the village, a cold reversal of the Biblical sacrifice of the son. He does not return for winter services that year, which the villagers interpret as "a sign of anger." When the pastor details that ridiculous masturbation story to Martin, the boy stands in front a cross in a clear reference to the key shot in Bergman's Winter Light. But where that film suggested the nonexistence of God, the implication of The White Ribbon is that He does exist; He's just an avaricious, self-absorbed bastard.

I do not think, however, that Haneke is really targeting God. Rather, he is attacking the idea of God as created by those entrusted to teach His word. The pastor does not come close to inhabiting the numerous atrocities committed in His name over the centuries, but his violent nature informs the wrathful image the villagers have of the Lord. Matthew 18:18 states that "whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven," so the God who treats Eichwald so cruelly is the result of the cruelty that forged Him. Curiously, I think of Jessica Rabbit from Who Framed Roger Rabbit: "I'm not bad. I'm just drawn that way."

Religion openly factors into the attacks, when the particularly repulsive attack on a mentally disabled boy is accompanied by a note that says the unidentified assailant shall continue to accost children as a means of atoning for their parents' sins. The note references the barbarous passage of Exodus 20:5, which reads, ""You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the fathers to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me." The next verse mentions that God will bless those who obey Him for a thousand generations, but the thought that He would take out his fury on the children of the wicked simply for being born is abhorrent.

The verse's use in this context raises a question: who is really being punished in The White Ribbon? The attack on young Sigi splinters the village across battle lines, between rich and poor as well as young and old. The adults beat their children to strengthen them, and those meant to help and advise them are either abusive (the pastor) or neglectful (the teacher). Even the doctor proves to be a monster, perhaps the worst of the all, when he returns; his kindness toward the other kids in the village belies the despicable, unspeakable ways in which he torments his midwife/mistress and his own children. The doctor's return collides so viciously with the longing and sorrow his children felt in his absence that he completely shifts the dynamic of their characters from loyal and loving children to codependent victims who do not have the power to change their lives and thus accept the conditions of their existence as best they can within traditional family behavior. The other kids in town are no better than the adults: the toughened children of the pastor and the Baron's steward eerily follow the trail of violence in the town under the pretense of helping the injured children and those of the injured adults as if an arthouse Children of the Corn. When someone brings to the attention of the pastor, who heretofore railed against the evils of the town children incessantly, he manages to locate a reserve of untapped hypocrisy to muster outrage at such an implication. How could anyone accuse the children? They're so innocent! Why, I even tied ribbons on them to remind them of how they're supposed to be!

The only rhythm to the attacks is that the weak are injured, which causes the strong to fear for themselves and thus take harsher measures against the weak, whom they set up as scapegoats. Thus, we see the young generation being hardened by horror, and that group of stronger children who follow the incidents around town will clearly grow into the sort of people who will embrace fascism in the detritus of Weimar Germany. It's plainly visible in Martin, who precariously walks the rails of a high bridge after his father beats him. When the schoolteacher catches him, Martin explains his behavior as a test of God's love; this moment demonstrates how the pastor's psychological warfare against the child's notion of his own spiritual worth leads him to desperately act out to see if God still loves him, but there's an almost Nietzschian arrogance in the response, as if this "proof" of God's decision to keep Martin alive proves his superiority. Like the religious angle of the film, however, I would hesitate to assign the film's violence to an explanation so simple as anti-fascism. Haneke himself placed the cycle of violence depicted in the film in the larger context of terrorism that such abuse breeds. For Haneke, children have suffered so much violence against them and perpetuated so much of their own that setting them in the fabricated glass cage of "innocence" is as detrimental as it is hypocritical. We turn our heads from this corruption so that these children grow up to repeat the cycle, especially when they live under an authoritarian system like the Baron's (or Hitler's).

Admittedly, that theme gives The White Ribbon a perilously clichéd premise, but anyone who truly pays attention to a film will know that what's being said counts for a lot less than how the filmmaker is saying it. The director does not show the violence, only the lead-up and the aftermath, studying how the acts affect others and how others continue to harm. Whenever a parent takes a cane to hit a child, Haneke stops his camera outside the room to spare us the sight. He does not, however, spare us the sound, the thwack of leather tearing air and ripping flesh as the most horrifying screams echo through the halls. The music is ominous and portentous, yet it is all diegetic, played by the sealed-off bourgeoisie who pound out such dolorous songs to distract themselves from the events plaguing the town even as the music itself makes it impossible to think of anything else. The sound design, deathly quiet and punctuated by the deafening sound of creaking wood and bloodcurdling screams, is every bit as impeccable as the cinematography, which itself gives away Haneke's method. By using color film and converting it in post-production to monochrome, Berger and Haneke prove that their intent with the film is not to recreate the period and delve into the characters but study them from a modern point-of-view. When Haneke cuts from the pastor intimidating his son with the masturbation story to a shot of the doctor screwing the midwife without passion just so he can get a jump (it's not even for something so seemingly quaint as pain suppression), the director underlines, with his typical dark humor, the insanity of instilling fear over something as harmless as self-love in the face of these cruel affairs conducted by the adults -- besides, is one-sided sexual gratification really so different from masturbation anyway?

That coldness might tie The White Ribbon to the director's usual detachment, but here he only condescends to the characters, and not the audience. There is a despair to this film, from the color being sucked out of its film stock to the flawless stoicism of the child actors, as Haneke attempts to show how deeply the corruption runs, how even children are being warped by a system of fascistic power-grabs that long preceded the National Socialist Party. And because he is willing to show the scope of society's oppression, Haneke is also shrewd enough to remind everyone that goodness still exists. Watch how he turns the overdone sentimentality of a young child, in this case the doctor's boy, asking about the meaning of death into something unique, heartbreaking, rewarding and even a bit scary by having the older sister, in her father's absence, try to explain this to the boy, whose birth cost their mother her life and whose father's uncertain state hangs over them both. Or, consider the scene where the pastor's young son gives him a bird that he nursed back to life as a replacement for his dad's lost pet, and how the pastor is quietly shamed by this act of the true innocence in which he does not really believe, that he commodifes with tacky symbolism and thus devalues until, for the rest, it becomes meaningless. These glimmers of hope can survive, but the sad truth is that the only way to do so, at least in the near future, is to simply flee the forces that identify humanity as a weakness and attack it. Who could blame the runners? Horror, like the other main forms of storytelling (action, comedy and drama), allows us to confront our fears in a safe environment. But Haneke does not allow us to simply accept these evils and move beyond them; he withholds the payoff, confronting us with the cracks in our society, not just the Nazis', and thus we are made to actually retain and ruminate upon what we see. Maybe that's why I had a panic attack in the parking lot.

Comments: 0

Post a Comment