Poetry, like Lee Chang-dong's previous Secret Sunshine, is suffused with cool blue, from the daytime sky to clothes to interior decorations. Not a single shot lacks this calming color, yet like Secret Sunshine, Poetry is a film of intense, devastating emotions and tragedies. Its very first scene drifts over from the idyll of children playing to a girl's corpse floating facedown in the river, and the story only becomes more wrenching from there. However, Lee does not use this juxtaposition of sunny visuals with dark narratives as an ironic counterpoint; his stories do not undermine the beauty of the world around them so much as make that beauty all the richer. Even in a world so besotted with ills, there is still unfathomable, almost spiritual grace and pulchritude.

More so than Secret Sunshine, Poetry stresses that point at every turn. The protagonist, Yang Mija (Yun Jeong-hee), lives on government welfare and the money she gets caring for an elderly man who cannot be but a few years older than her. From the moment we meet her, Mija displays a troubling forgetfulness of words, and when she goes to a clinic to get her arm checked, the doctor on-hand sends her to Seoul to have her head examined. Her own problems are bad enough, but certain revelations threaten to send the film into an abyss of pain. But Poetry is a film about perseverance, of passing through the terrible sights right in front of us to experience that glorious world around us. Naturally, art is the means of seeing the full picture, yet Lee does not use expression to simplistically ignore the reality it transcends.

Mija, a kind woman with preserved beauty, decides to keep her mind working by enrolling in a poetry class, where she reacts to the instructor's metaphorical instruction with an almost childlike literalism, interpreting his talk of poetic inspiration as a goal to be achieved rather than a state of mind. But she cannot probe deeper into the reality of being because her meekness causes her to sweetly but unmistakably retreat from the world. Not that she doesn't have good reason to: already dealing with her early-stage Alzheimer's, Mija must also contend with her unruly grandson, Wook, who runs with a rough crowd of five equally rude and terse boys. One day, the parents of those boys invite her to lunch, where they reveal the sickening fact that this silly gang had something to do with the aforementioned girl's suicide. The adult men look for some excuse, any excuse, to shift even some of the blame off their sons, and they have already set in motion a plan to buy off the girl's family to protect everyone's honor. Coerced into cooperating, Mija can only numbly agree, able to contain her sorrow and anger only by ignoring it where possible.

With a graceful, patient approach to pacing, Lee lets the poor woman languish for a while without losing the overall thread of the story. Still hunting inspiration as if buried treasure, she occasionally spouts poetic verse without realizing it. "But nouns are most important!" she says with a heartbreakingly mirthless laugh when a doctor officially diagnoses her dementia and says she will first forget basic nouns, yet that same hindrance allows Mija to circumnavigate the nominal in the manner of a true poet. However, these flashes are short-lived, the engine turning over but never quite starting. Here Lee makes his clearest commentary: her gasps of poetic license tend to come when she starts to approach her situation, not confronting her predicament but at least gearing up to do so. The men send her to plead with the girl's mother to accept their hush money, but when Mija meets the woman out in a field, she ends up waxing on apricots and flowers, saying beautiful things but never getting around to the reason why the two are talking. That fleeting capacity for art fades when she follows its loftiness away from the necessity of facing up to her real issues. Art may work as escapism, but it cannot do so for long. Indeed, it is not until the end, when Mija makes a sudden decision to truly resolve her grandson's situation that she can craft a poem that at once captures reality and breaks through it to deeper levels of truth.

Lee's direction similarly seeks a balance between an honest appraisal of the world—achieved through primarily static takes that run long enough to capture nuanced, realistic gestures and actions—and a more visually eloquent portrait, created with his gorgeous, singular use of hyperreal color. A shot of raindrops hitting a notebook is so perversely ordered in its chaos that it almost resembles animation, each drop blotting the naked page as if ink splattering. One briefly recurring scene places the members of the poetry class one by one at the head of room, each describing "the most beautiful moment" of his or her life. Notably, all of the stories are rooted in deep pain or hardship, be it an agonizing pregnancy and delivery or the small victory of a man who lived in a basement his whole life finally saving up enough to afford his own apartment. The point of this exercise is clear: to find an abstract inspiration from a concrete memory, to link the overcoming of pain with the overcoming of prosaic senses.

The film's coda is certainly a transcendance of the previously realistic events, an ambiguous, ethereal montage that suggests death and resurrection, or maybe even an alteration of reality through the power of art, the poet literally taking the place of the subject. Maybe the most haunting yet lyrical narrative break since the achingly heartwarming what-if? montage that closes 25th Hour, Poetry's final minutes show the clear hand of a novelist, willing to challenge the audience by setting aside narrative consistency so that the style becomes the theme. In a film comprising nothing but poignance, this conclusion is the most poetic and affirming statement of all.

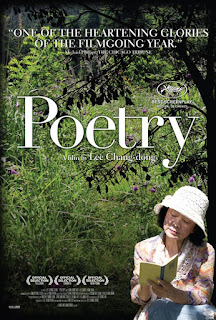

Poetry (Lee Chang-dong, 2011)

Comments: 0

Post a Comment